All across parts of western and central Illinois, people are showing up to knock on landowners’ doors, maps in hand and dollar-figure promises at the ready. They represent Navigator CO2 Ventures, and they want to lay 250 miles of carbon dioxide pipeline across parts of 11 counties, ending in Christian County. That’s where the CO2 from ethanol and fertilizer plants in Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota and Minnesota would be funneled underground and stored.

All told, they want to lay 1,300 miles of 20-inch pipeline buried 5 feet underground and collect CO2 from nearly three dozen different fertilizer and ethanol plants, to capture and store 15 million metric tons of CO2 a year. It’s a $3.2 billion project, called the Heartland Greenway.

As you might imagine, folks in Illinois are skeptical about this proposition.

The Coalition to Stop CO2 Pipelines, Citizens Against Heartland Greenway Pipeline (annual membership is $500) and more have mobilized. Even the Sierra Club is against it.

Heartland Greenway filed an application for approval with the Illinois Commerce Commission in July, but just last week withdrew it. Some groups claimed victory thanks to landowner opposition, but Navigator said not so fast. They withdrew in order to reorganize and expand the pipeline footprint they’re requesting. Stay tuned for new maps.

But back to the storage. Why bring CO2 from five states to Illinois anyway?

It’s called the Mount Simon Sandstone geological formation. Those underground rock formations make Illinois a geological marvel and one of the better places in the U.S. to store carbon. Rod Weinzierl at IL Corn calls it a natural resource that’s waiting to be tapped.

Below our beloved Illinois topsoil lie layers of solid rock formations, called the Illinois Basin, which also extends into parts of Indiana and Kentucky. North of Bloomington and in Champaign County, natural gas is pumped and stored under the first layer of rock, so when winter demand increases, natural gas can be pulled from those regions instead of piping it in. Coal shaft mines are typically located below the first rock layer; they use that layer for the mine roof.

The Mount Simon Sandstone formation is three solid-rock layers down, about 1.25 or 1.5 miles underground. That’s what makes this region unique. And valuable.

That means Illinois landowners need to brace up. Because regardless of what any of us believes about greenhouse gas emissions or carbon credits or anything else relative to climate change, this conversation will continue to amp up in the coming years. And the pipelines will point to the Mount Simon Sandstone in Illinois.

Tried and tested

Archer Daniels Midland and the Illinois State Geological Survey at the University of Illinois have spent the past 10 years researching and testing the possibility of storing carbon underground, in a project known as the Illinois Basin-Decatur Project. Over three years, they captured 1 million metric tons of CO2 from the ADM ethanol plant at Decatur and injected it into the Mount Simon Sandstone, more than a mile and a quarter deep in the Illinois Basin.

If you’ve walked the Farm Progress Show site, you’ve walked above stored carbon.

Sallie Greenberg, ISGS principal investigator on the project, says they’ve created a project that produced valuable data for researchers around the world. Indeed. They carried out one of the largest carbon sequestration projects in the U.S., demonstrating that it’s entirely possible to capture and store carbon.

But can you pipe it across a thousand miles? That’s a different question, and one the opposition groups are asking. They’re also asking what’s in it for the landowner, and folks in the ethanol business have an answer for that one.

Corn economics

All around the world, countries and industries are talking about carbon scores. Markets are beginning to develop based on the carbon scores of products. In the U.S., the Renewable Fuel Standard rewards fuels with a lower carbon score. It’s creating a value that’s not defined by dollars, at a very high level.

And it matters for ethanol, Weinzierl says. “Anything we can do to reduce the carbon score for ethanol makes ethanol not only more competitive from a price standpoint, but also from a greenhouse gas emission reduction standpoint. That will be big over the next couple decades.”

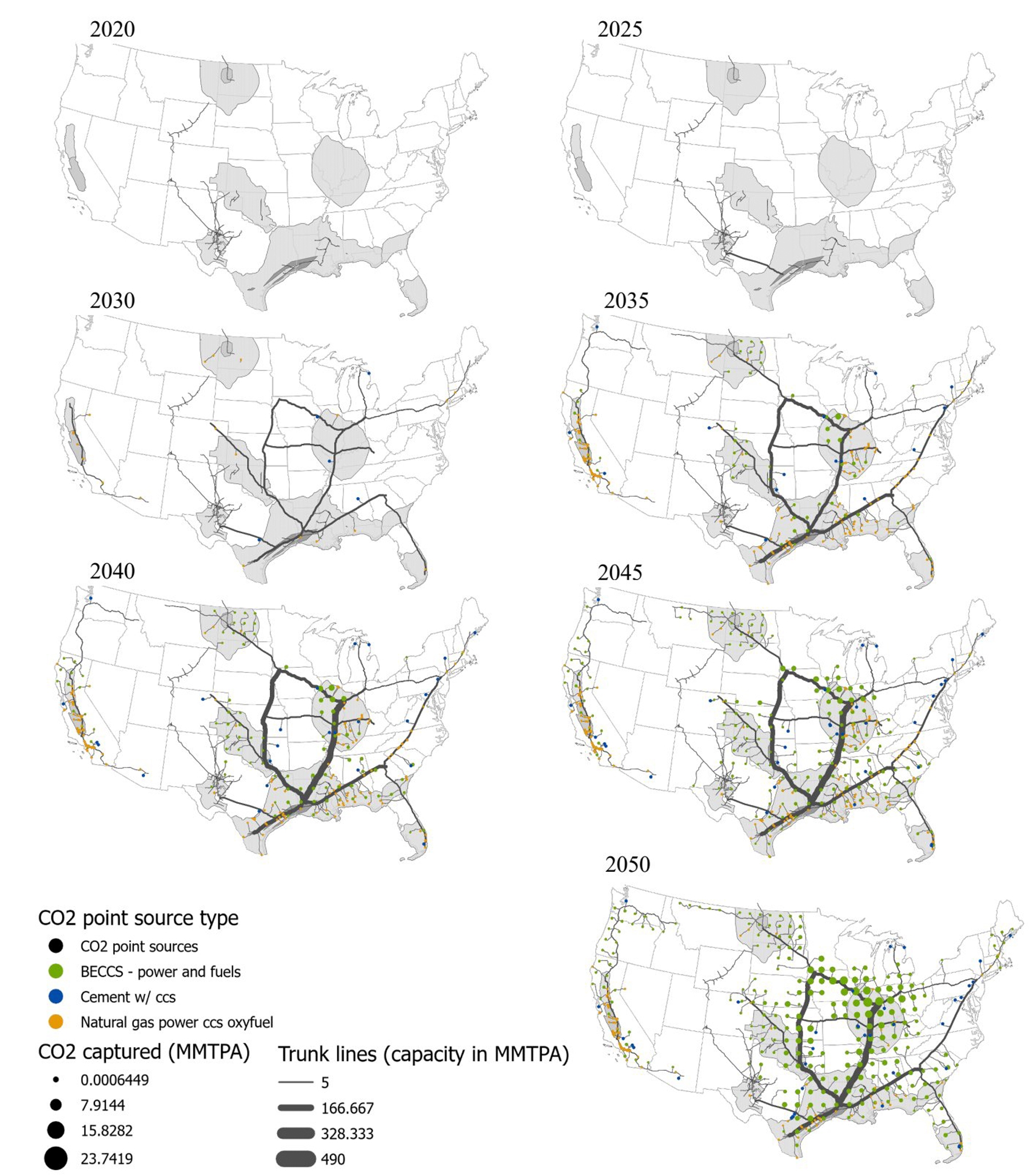

EXPANSION: A 2020 Princeton University study shows a possible transition for CO2 capture and transport across the U.S., from 2020 to 2045. (Images courtesy of Princeton University)

The Illinois General Assembly recently passed a tax credit on sustainable aviation fuel, where $1.3 billion gallons are used every year — nearly the same as diesel. Aviation fuel companies are interested in building in Illinois, near where carbon can be stored.

Weinzierl even thinks the Mount Simon Sandstone resource will reopen the door to siting anhydrous production facilities in Illinois, which produce a tremendous amount of CO2 as a coproduct. Build here and they could store that CO2. That would create a low greenhouse-gas-emission nitrogen source.

Imagine for a minute that you could apply a low greenhouse-gas-emission nitrogen to your crop. It takes more Btu of nitrogen to produce corn than any other energy input. You would effectively lower the greenhouse gas footprint of everything that corn goes into, including ethanol and meat.

And what ever would the Meatless Monday folks complain about then?

“Illinois has a really valuable resource that a lot of other locations in the U.S. don’t have,” Weinzierl explains. “People will try to capitalize on that resource to help them in this future trajectory of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

But to do that, you’ve gotta get the CO2 from where it’s produced to where it’s sequestered. And how do you do that?

Pipelines.

That, my friends, is why CO2 is dominating the conversation in Illinois. And why — like it or not — it’s not going away anytime soon.

Comments? Email holly.spangler@farmprogress.com.